EU Funding for NGOs- Value for Money? Part II- an Echo Chamber

The following is the second in a series of three reports, addressing the issue of “value for money” in EU funding to NGOs. The first report dealt with structural issues of EU funding, such as the multiplicity of funding instruments and overlapping objectives. The following report will focus on the EU’s engagement with civil society, highlighting phenomena such as centralization among grantees, EU-funded advocacy networks and involvement of NGOs in policy-making.

The following is the second in a series of three reports, addressing the issue of “value for money” in EU funding to NGOs. The first report dealt with structural issues of EU funding, such as the multiplicity of funding instruments and overlapping objectives. The following report will focus on the EU’s engagement with civil society, highlighting phenomena such as centralization among grantees, EU-funded advocacy networks and involvement of NGOs in policy-making.

Click for PDF version of this report.

Executive Summary

- The relationship between the European Union (EU) and civil society is marked by an unbalanced distribution of funding, favoring a small number of highly interconnected NGOs. The EU and NGOs rely on one another for information, creating a closed echo chamber, undisturbed by any external input or independent evaluation.

- The EU regards NGOs as authentic and reliable representatives of civil society, without employing any measures to ensure that this is indeed the case.

- The concentration of EU funding among a narrow segment of civil society expands the influence of these groups in a manner that does not necessarily reflect the public interest or democratic norms. This happens on an international and a local scale, and in both donor and recipient countries.

- EU funding also inflates NGO representation in the EU’s decision-making processes, due to EU reliance on self-reported, unverifiable information from a limited number of sources. The EU and NGOs repeatedly cite one another in publications.

- The biggest beneficiary NGOs are highly interconnected – with overlapping memberships in multiple networks and shared board members.

- NGO funding is the result of, as well as the enabler of, lobbying – leading to yet more concentration of funding. The EU also directly funds lobbying networks whose mission is specifically to lobby the EU for money.

- Recipient NGOs and EU donor frameworks are highly interdependent, lending each other legitimacy irrespective of substantive impact.1

EU Engagement with Civil Society

The European Union (EU) consistently endorses a deep engagement with civil society for a number of reasons. As argued in the EU’s White Paper on European Governance in 2001: “civil society plays an important role in giving voice to the concerns of the citizens and delivering services that meet people’s needs. […] It is a chance to get citizens more actively involved in achieving the Union’s objectives” (p.6, emphases added).

The EU commissions civil society for service provision. EU humanitarian aid, for example, is implemented solely via partner organizations, of which 46% are NGOs. Because of their role as service providers, partner organizations – especially in the field of external aid – are also viewed as the go-to experts on policy implementation. As explained on the website of the Directorate General for International Cooperation and Development (DG-DEVCO): “civil society organisations (including NGOs) are vital partners for decision-makers, as they are best placed to know population’s needs in terms of development. […]The role of civil society organisations/Non-State Actors is growing from being implementing partners to sharing more responsibility with the state” (emphasis added).

The EU has no clear criteria to ascertain which organizations truly represent public opinion and interests or are suitable for the provision of specific services. This is specifically acknowledged in a communication from the European Commission in 2002: “problems can arise because there is no commonly accepted – let alone legal – definition of the term ‘civil society organisation’” (p.6). Despite this, NGOs continue to be viewed as authentic representatives of civil society, and as trustworthy, expert policy implementers. In addition, the EU does not sufficiently take into account the importance of ensuring a broad representation of constituencies reflecting the full diversity of public discourse.

In 2000, the Commission issued a discussion paper entitled: “The Commission and Non-Governmental Organisations: Building a Stronger Partnership.” As correctly identified in the paper, “increasingly NGOs are recognised as a significant component of civil society and as providing valuable support for a democratic system of government. Governments and international organisations are taking more notice of them and involving them in the policy- and decision-making process” (p.4, emphasis added).

The strategy for the EU’s engagement with NGOs laid out in 2000 by this discussion paper is still pursued and remains unchallenged. The result is that NGOs – more often than not, highly professionalized, well-established and interconnected in transnational advocacy networks – are regularly consulted with, as well as funded by, EU institutions. The following will demonstrate the practical and ethical implications of these assumptions and practices.

Centralization in European Civil Society

While the underlying argument for the EU’s engagement with civil society is enhanced democratic representation, funding figures reveal a high degree of centralization among EU NGO grantees. This narrow distribution leads to a distorted representation of civil society on the EU level that does not necessarily reflect public interest, rendering the notion of “support for a democratic system of government” unfounded.

Research conducted by think-tank “New Direction” in 2013 revealed that in 2010, out of nearly 2,000 NGOs that received almost €1.5 billion in grants, €1.12 billion went to only 273 NGOs receiving more than €1 million each. These include Oxfam (€43.6 million), Save the Children Fund (SCF) (€34.1 million), Concern Worldwide (€31.7 million), Action Contre La Faim (€24.4 million) and Deutsche Welthungerhilfe (€24.4 million) (p.12). During 2002-2004 the three largest recipients among environmental organizations received about 70 times more than the three smallest; funding for seven out of the 39 NGOs accounted for more than 50% of the total funding, and funding for 14 NGOs accounted for 75% (p.14).

The interconnections between leading grantees also point to centralization on deeper levels, as demonstrated by double and triple memberships in overlapping NGO networks. Unlike member NGOs, which implement projects requiring large budgets, these networks have smaller budgets designated almost exclusively for advocacy and lobbying decision-makers.

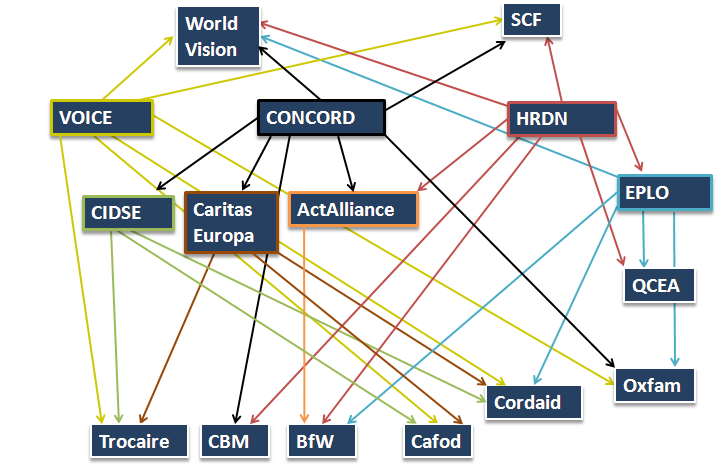

Perhaps the two largest networks are CONCORD and VOICE– two European NGO confederations for development and humanitarian aid, respectively, both of which receive regular EU funding and consider themselves “the main interlocutor with the EU” in their respective fields. CONCORD’s members are themselves NGO networks such as Oxfam, CIDSE, Caritas Europa, CARE International, World Vision, and SCF, as well as national NGO networks such as VENRO (Germany) and Dochas (Ireland). VOICE members include country branches of these networks, as well as several independent NGOs such as the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). Other networks are the Human Rights and Democracy Network (HRDN) and the European Peacebuilding Liaison Office (EPLO), whose members include Brot für die Welt (BfW), Christian Blind Mission (CBM), and the Quaker Council for European Affairs (QCEA). The majority of these organizations receive EU funding.

Overlapping memberships in NGO networks

An example of membership in multiple EU-funded networks is the following: Irish Catholic aid organization and EU grantee Trocaire is a member of three CONCORD networks – Caritas Europa, CIDSE, and the Irish national NGO network Dochas – in addition to its membership in VOICE. With the exception of CIDSE, all of these receive EU funding. According to the EU’s Financial Transparency System (FTS), Trocaire received €11,004,803 from the EU in 2014, Dochas €111,650, and Caritas Europa €1,464,352. CONCORD and VOICE are not listed in the FTS, but according to the EU’s Transparency Register, CONCORD received over half of its annual budget and all of its public funding (€700,000) from the EU in 2015; VOICE received roughly 40% of its budget and all of its public funding (€200,000) from the EU in 2014 (latest available information, accessed June 2016).

A review of CONCORD’s board members also reveals interconnections at the level of personnel. While CONCORD board members supposedly represent their respective member organizations, many in fact have worked, sometimes simultaneously, for several member NGOs – most of which receive EU funding. Thus, the interests represented in CONCORD are considerably narrower than the number of members would suggest:

- CONCORD’s director Seamus Jeffreson has worked previously with CARE, Trocaire, and CAFOD. CAFOD, a UK-based catholic aid organization is, like Trocaire, a member of CIDSE and Caritas Europa. According to the FTS, CARE International received €1,584,990 from the EU in 2014 and CAFOD €7,774,634 in 2013.

- CONCORD board member Izabella Toth was elected as representative of CIDSE and is simultaneously chair of the CIDSE/Caritas Europa EU-co-financing group, as well as Senior Corporate Strategist in Cordaid, another member of Caritas Europa and CIDSE. According to the FTS, Cordaid was the recipient of €1,587,140 from the EU in 2014.

- CONCORD board member and treasurer Marius Wanders, who was elected as representative for World Vision and is International and Executive Director of World Vision Brussels & EU Representation, previously served as Secretary General and Chief Executive of Caritas Europa. According to the FTS, country-based branches of World Vision received over €15 million from the EU in 2014.

Centralization in Non-European Civil Society

The EU’s engagement with NGOs involves extensive activities overseas. As stated in the Commission’s 2000 discussion paper on NGOs: “the major part [of NGO projects is] in the field of external relations for development co-operation, human rights, democracy programmes, and, in particular, humanitarian aid” (p.2, emphasis added). As elaborated later in the paper: “Developing and consolidating democracy is also the Community’s general policy objective…Partnerships with local NGOs in developing countries are particularly significant in this regard” (p.4, emphasis added).

The centralization in EU-funded European civil society directly translates into centralization in recipient countries. NGO Monitor analysis of funding to Israeli NGOs identified the EU as the single largest donor to a select group of similarly affiliated NGOs active in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – with NIS 28,196,067 allocated to 27 such NGOs in 2012-2014. The vast majority of donations to these groups – NIS 129,287,704 in the same period – comes from European governments, directly and indirectly. These organizations resemble each other in their activities and agendas, as well as in their affiliations and partnerships.

An analysis of a series of seven EU grants to Israeli NGOs in 2015-2016 revealed a striking level of interconnectedness between the recipients – all of the recipients were also grantees of the New Israel Fund, and shared several board members. One NGO, the Association for Human Rights in Israel (ACRI), was in fact the recipient of two EU grants – one directly, and one as a co-recipient with another organization. This information was absent from the EU’s publication of the grant, and could only be retrieved from the organizations’ websites.

Perhaps more than direct funding, centralization at the local level results from indirect EU funding through well-established European NGOs such as those surveyed above, which channel money to local NGOs. A prominent example is EU funding to the Norwegian Refugee Council for the project “Information, Counselling and Legal Assistance (ICLA) for increased protection and access to justice for Palestinians affected by forced displacement in Palestine.”

The NRC is a major EU grantee – in 2014 it received over €35 million. Its ICLA project in the West Bank and Gaza was launched in 2009 and has enjoyed a steady rise in EU funding ever since, as shown in the table below. In addition to the EU, this project is also funded by the British, Norwegian, and Swedish governments. (For more information on issues of transparency and accountability regarding this project see Part I of this series of reports. For more information on ICLA activities, see NGO Monitor’s 2014 report.)

According to its website, the NRC funds “7 NGOs to provide direct legal aid” as part of the Palestinian ICLA project – but their identities are not disclosed. However, in 2012-2014, three Israeli NGOs reported NRC funding to the Israeli Registrar for each year – Bimkom, Hamoked, and Yesh Din. All three were also EU and Oxfam grantees for the same time period, and Yesh Din also received funding from CAFOD for each consecutive year. As revealed by NGO Monitor analysis, Yesh Din is the Israeli NGO with the highest relative share of foreign government funding – 93.5% of its budget comes directly and indirectly from foreign governments in 2012-2014.

EU Funding to NRC’s ICLA Project:

| Year | Amount |

|---|---|

| 2009 | €700,000 |

| 2010 | €1,365,000 |

| 2011 | 1,400,000 |

| 2012 | €1,400,000 |

| 2013 | €1,600,000 |

| 2014 | $4,340,509 |

*All data from the FTS other than the last entry, which is from UN-OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service.

EU Rhetoric of NGO Representation

As the EU involves a select group of NGOs in its decision-making, centralization affects policies that have major international impact. Rather than addressing this issue and examining the evidence systematically, EU officials simply claim that NGOs are a balancing force that empower weak members of society: “In particular, many NGOs have an ability to reach the poorest and most disadvantaged and to provide a voice for those not sufficiently heard through other channels… In some cases, they can act as a balance to the activities and opinions of other interests in society” (Commission discussion paper on NGOs, p. 5, emphasis added). However, as evidenced above, the EU’s engagement with select NGOs reflects a narrow set of interests and opinions.

The Commission’s discussion paper on NGOs dedicates one paragraph (p.9) to the issue of representation, addressing it in incoherent, vague, and contradictory terms. While asserting the importance “for NGOs and groupings of NGOs to be democratic and transparent as regards their membership and claims to representativeness,” the paper links this to “work(ing) together in common associations and networks at the European level since such organisations considerably facilitate the efficiency of the consultation process.” As shown above, this clustering into associations and networks is inconsistent with the claim to promote diverse and balanced representation via NGO links. Instead, it merely enables like-minded and well-established organizations to exert influence without accountability. Contradicting the earlier emphasis, the section concludes: “representativeness, though an important criterion, should not be the only determining factor for membership of an advisory committee, or to take part in dialogue with the Commission.”

Similarly, in her article “Civil society and EU democracy: ‘astroturf’ representation?” (2010), German scholar Beate Kohler-Koch asserts that “the rhetoric of CSOs and the explicit request of EU institutions convey an image of representation that is in contrast with reality” and that “European CSOs are distant from stakeholders, in the case of NGOs even more so.”2

EU Dependence on NGOs for Information

The EU both consults with and relies on NGOs for factual information and analysis, as reflected in EU policy statements and documents. However, the evidence indicates that the credibility of NGO information is neither methodically verified nor questioned by the EU (detailed in NGO Monitor’s report).

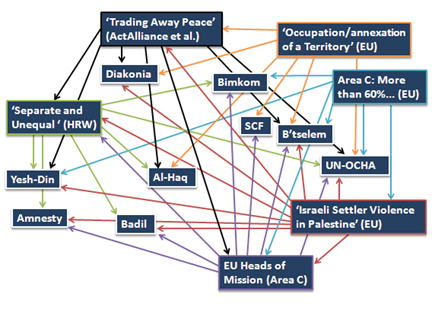

Below is a depiction of this echo-chamber, as found in four EU reports and two NGO documents that cite the same NGO sources: EU Heads of Mission report ‘Area C and Palestinian State Building’ (2011); European Parliament (EP) policy briefing ‘Israeli settler violence in Palestine’ (2012); EP policy briefing ‘Area C: More than 60% of the occupied West Bank threatened by Israeli annexation’(2013); and EP study ‘Occupation/annexation of a territory: Respect for international humanitarian law and human rights and consistent EU policy’(2015). The two NGO reports are ‘Separate and Unequal: Israel’s Discriminatory Treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories’ (2010) by the NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW); and ‘Trading Away Peace’ (2012), a report issued jointly by 22 major European NGOs, among them Trocaire, Cordaid and the network ActAlliance of which Diakonia (see graphic) is a member.

As an example, four out of six of these publications – HRW’s Separate and Unequal; the joint NGO publication Trading Away Peace; and the two EP policy briefings, on Area C and on settler violence respectively – cite the same finding reported by Yesh Din in 2010 and 2011, according to which “90% of investigations of Israeli attacks against Palestinians are closed without indictments.” However, data from the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (tables 11.3 and 11.4) demonstrate that in 2011 the Israeli police opened a total of 364,730 files, with 38,334 indictments (10.5%) –indicating that the low indictment rate is by no means reserved to cases of violence against Palestinians. Moreover, according to the EU’s statistic database, similar indictment rates were recorded in Sweden (9.59%), Malta (10.06%) and Norway (10.09%) in 2012. This information paints an altogether different picture to the one depicted in the above-mentioned publications, clearly indicating a lack of methodical verification or critical analysis by the authors.

The reliance on NGOs as information providers is demonstrated even when ostensibly non-NGO sources are cited. Of all the sources appearing in the graphic above, only the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN-OCHA) is not an NGO. However, UN-OCHA reports cite NGOs extensively. For example, the UN-OCHA report ‘Restricting Space’ (2009), is cited by three out of six of the publications above (the EU Heads of Mission report, HRW’s report and the EP briefing on Area C), and includes 19 references to Israeli NGO Bimkom (quoted by 3 out of 6 of the above-mentioned publications).

The centralization process is also manifest in the local NGOs cited in these reports. Many are in fact partnered with major European NGOs. For example, Diakonia (member of ActAlliance and signatory to ‘Trading Away Peace’) partners with Badil and Al-Haq. Trocaire (member of CIDSE and Caritas Europa, also signatory to ‘Trading Away Peace’) partners with Badil, Al-Haq, B’Tselem, and Hamoked.

Lobbying for Money with EU Funding

NGO networks do not only collaborate in order to better advocate for their respective agendas, but also to influence the EU budget – in other words, to lobby for money. This indicates a process of centralization that only enhances with time and deepens the gap between represented and unrepresented civil society. As quoted above, “the European Commission encourages organisations to work together in common associations and networks at the European level since such organisations considerably facilitate the efficiency of the consultation process” (Commission discussion paper on NGOs, p.9).

However, the EU’s support to these networks goes well beyond encouragement.

CONCORD has a ‘Funding for Development and Relief (FDR) Working Group,’ which focuses on “NGO funding policies and priorities, on the allocation of funds to these priorities and on the European funding process and organisation” (emphasis added).

HRDN has a ‘Funding for Human Rights and Democracy Working Group,’ which “follows the programming and implementation of the EU funds supporting actions on human rights and democracy, in particular the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR), with a view to increasing the effectiveness of the EU financial support to human rights defenders and civil society organisations in the EU’s partner countries” (emphasis added).

EPLO has a Funding for Peacebuilding Working Group that aims to ensure an “increase in the amount of EU resources which are specifically allocated in support of civilian peacebuilding and conflict prevention activities and that peacebuilding and the prevention of violent conflict are mainstreamed throughout the EU’s external financing instruments” (emphases added). EPLO also has a Civil Society Dialogue Network (CSDN) – “a mechanism for dialogue between civil society and EU-policy-makers… co-financed by the European Union (Instrument for Stability) and EPLO, and managed by EPLO in co-operation with the European Commission (EC) and the European External Action Service (EEAS).”

Social Platform, a network of European social NGOs, states that its aim is to “orient the decisions on the EU budget towards the interest and well-being of people. We have developed proposals to ensure that the EU budget for the years 2014-2020 provides adequate funding …we are also asking to be recognised as full partners, together with regional and local authorities, and social partners in all the phases of the programmes” (emphases added).

With the exception of HRDN, all of the above networks are funded by the EU, as reported in the EU’s Transparency Register. The main mandate of these networks is to lobby the EU for funding.

In addition to lobbying networks, it is safe to assume that many EU grantees utilize their funds to lobby the EU for additional money. Funding figures indicate that this is an effective method. The above-cited 2013 research of think-tank “New Direction” found that 86% of EU grants are awarded to NGOs headquartered in Brussels, and on average these NGOs receive grants twice as large as the total average (p.6). The examples above, however, are not simply cases of funding indirectly utilized for lobbying, but of EU funding directly and explicitly designated for this purpose.

Unfounded Legitimacy

It is apparent that EU funding to NGOs is not only meant to support NGO projects. It is also highly beneficial for the self-promotion and publicity of both the EU and its beneficiaries. The EU utilizes project funding for positive publicity. According to the Commission discussion paper on NGOs: “[NGOs’] involvement in policy shaping and policy implementation helps to win public acceptance for the EU” (p.5). In 2010 the EU issued a Communication and Visibility Manual for European Union External Actions, “designed to ensure that actions that are wholly or partially funded by the European Union (EU) incorporate information and communication activities designed to raise the awareness of specific or general audiences of the reasons for the action and the EU support for the action in the country or region concerned, as well as the results and the impact of this support.”

The manual suggests the use of “key messages” such as the following: “The world’s biggest donor at the service of the Millennium Goals”; “More, better, faster – Europe cares”; “The EU and <partner NGO> – delivering more and better aid together” and “cooperation that counts” (p.30, parentheses in the original).

The Commission’s Directorate General for humanitarian aid and civil protection (ECHO) offers an extra budget for partners wishing to opt for “above-standard visibility” – this could include “audio-visual productions, journalist-visits to project sites, billboard campaigns, exhibitions or other types of events with an important outreach to the European public and media.”

The recent review of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) from November 2015 sets “visibility, communication and outreach” at “the heart of the new ENP” – “An appropriate mix of proactive strategic and tactical communication tools will allow the EU and its partners to better monitor and analyse the media, to better understand perceptions and narratives in the partner countries and to explain the benefits of each country’s cooperation with the EU with the ultimate goal of creating a positive narrative about support and cooperation under the ENP” (emphasis added).

In 2015, the EU issued a €400,000 call for proposal entitled “Cultural Diplomacy – Palestine,” whose explicit objectives are to “ increase public awareness of EU core values and enhance visibility of the EU cooperation in Palestine through cultural diplomacy… ensure maximum EU public outreach, in both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, by participating in major Palestinian cultural events, performances, and festivals.” This project was financed by the EU’s European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR).

Through extensive funding, the EU makes a reputation for itself as a generous aid donor around the world, while NGOs enjoy cash flow and a foothold in EU institutions, as well as top-down establishment approval as credible, trustworthy organizations. However, this double-sided legitimacy is not based in substance. Rather, it is the result of a hermetic echo chamber, in which the relationship between the EU and NGOs is conducted with virtually no external input.

Footnotes

- The EU-NGO interdependent relationship is analyzed by Gerald M. Steinberg, “EU Foreign Policy and the Role of NGOs: The Arab-Israeli Conflict as a Case Study”, European Foreign Affairs Review 21:2, 2016 p.251-268

- For additional academic discussions and analysis, see article by Steinberg, footnote 1 above