No NGO Left Behind: The Politics of OCHA’s COVID-19 Humanitarian Aid in the West Bank and Gaza

Click here to view the full PDF

Introduction

On March 27, 2020, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO), announced the “oPt Inter-Agency Response Plan for COVID-19.” OCHA requested $34 million on behalf of numerous UN agencies1 as well as local and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for use in the West Bank and Gaza. This number was raised to $42 million in late-April.2

OCHA’s NGO partners include Health Work Committees (HWC), Union of Health Work Committees (UHWC), Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC), Union of Palestinian Women’s Committees (UPWC), and Palestinian Center for Human Rights (PCHR) – which are all tied to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) terror group3 – as well as advocacy groups such as Yesh Din, Al Mezan, Adalah, and HaMoked.

In its fundraising efforts, OCHA stated that additional resources were needed to “respond to the public health needs and immediate humanitarian consequences of the pandemic in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip” (emphasis added).

However, many of the activities being attributed to the Plan – as detailed in periodic “Situation Report” updates from OCHA and discussed below – do not appear to involve vital, lifesaving resources and supplies “to implement the most urgent and critical activities.” In some instances, it is clear that existing NGO advocacy ventures, which often involve anti-Israel rhetoric and agendas, have been relabeled “COVID-19,” without a substantive contribution to emergency humanitarian aid. Furthermore, some of the descriptions of NGO activity indicate low- or no-cost efforts, and/or tasks that had already been performed – although there is no information about how much money the NGOs were receiving.

This suggests that key factors for OCHA are the goals of procuring funds for their NGO allies and “padding the stats” – not providing critical humanitarian materials in the most efficient and professional manner possible. Similarly, the listing of independent donations from “outside the Response Plan” (see “Donor Governments” below) and NGO activities that were not part of the original strategic document reflect OCHA’s attempt to take credit for others’ work and inflate its importance and centrality.

Moreover, the call for “emergency” funds comes after OCHA, other UN and development agencies, and their NGO partners have spent millions on anti-Israel advocacy agendas. For years, detailed analysis shows that these groups have prioritized targeting Israel over humanitarian aid, including through official UN partnerships with the Palestinian Authority (i.e. UNDAF). The COVID-19 crisis is exposing how wasteful and counterproductive this approach has been.

Donor Governments and OCHA’s Political Agenda

In its Situation Reports, OCHA provides varying details about donations for humanitarian aid, reflecting a manipulation of data to create the illusion of robust fundraising and implementation of the Response Plan. In reality, OCHA was taking credit for funding and projects not under its aegis.

It is also unclear whether donors can exercise adequate supervision over the spending, in particular since a number of PFLP-linked NGOs are involved and the UN does not respect the donor governments’ restricted terror lists. Officials from UNICEF,4 one of the Response Plan’s implementing partners, thanked donors for their provision of “flexible funds” (see tweets from UNICEF’s Special Representative in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza and UNICEF’s Executive Director). OCHA also refers to “the reprogramming of funds previously allocated or pledged for other interventions” (see below for more details). Both terms suggest willingness by at least some of the donor governments to forgo necessary safeguards, due diligence, accountability, and oversight during a crisis.

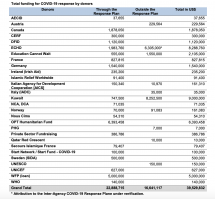

According to OCHA, as of May 11, $21.2 million has been raised for activities within the response plan, and a total of $37.9 million for all “COVID-related response activities in the oPt.” Overall, the largest donors to the COVID-19 response in the West Bank and Gaza are Kuwait, EU (ECHO), Canada, the UK (DFID), Sweden, Ireland, Norway, and Spain (AECID).

Source: Screenshot of “Occupied Palestinian Territory (oPt): COVID-19 Emergency Situation Report No. 9 (May 12 – May 18 2020),” page 5.

As seen in this table, the majority of funding is for activities “outside the Response Plan” – meaning not connected to the COVID-19 plan coordinated by OCHA – and not from new commitments, but rather from “the reprogramming of funds previously allocated or pledged for other interventions.” Earlier iterations of OCHA’s data only distinguished between “new” and “reprogrammed” (apparently from donor contributions to the region but for alternate projects) money. However, the language was altered in the April 14-20 report, where funding was separated into categories called “through the response plan” and “outside the response plan.”5 These changes are not noted as corrections after donors flagged OCHA’s claims, but are instead construed as “more detailed information from donors and recipient organizations.”

NGO Partners

In implementing its COVID-19 emergency response plan, OCHA is working with numerous local partners – international, Israeli, and Palestinian NGOs that are supposedly tasked with carrying out projects related to combating the spread of the virus. As a whole, many of the activities appear to be tangentially related to the COVID-19 emergency, and others are not humanitarian at all. The following is a selection of such NGO activities; the OCHA website includes countless more examples.

Terror-Tied NGO Partners

In sharp contrast to the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence, OCHA partners with a number of organizations that have ties to internationally designated terrorist organizations, some of which have staff members that have been involved in deadly attacks. Financial support to these groups results in increased risk for aid diversion.

Health Work Committees (HWC) and Union of Health Work Committees (UHWC)

Both HWC and UHWC are listed as working within the “Health and Nutrition Cluster” on projects related to stopping “further transmission of COVID-19 in the oPt,” providing “adequate care for patients affected by COVID-19…their families and close contacts,” and “mitigat[ing] the impact of the epidemic.” The April 13 OCHA Situation Report mentions HWC and UHWC in at least four projects working on “Establishment of medical triage areas for suspected cases of COVID-19,” training staff “on the provision of basic emotional and practical support to affected people,” providing “Equipment of an intensive care unit room,” and the printing of awareness materials.

HWC also worked with CARE International and Palestine Red Crescent Society to provide “supplies and disposables to facilities and training to 24 medical teams. Re-printing health education and awareness materials and utilizing social media and radio stations for raising awareness on COVID-19,”among other activities. HWC provided “dignity kit for women,” targeting three beneficiaries.

- In this context, it is important to note that in October 2019, Waleed Hanatsheh, HWC’s “Financial and Administrative director,” was arrested for participating in a PFLP-led terrorist attack in which a 17-year old was murdered. According to his indictment, Hanatsheh bankrolled the PFLP cell. Hanatsheh is currently standing trial for the murder.

- UHWC is identified by Fatah as a PFLP “affiliate” and in a 1993 USAID-engaged audit report (by the Democratic Institutions Support Project) as “the PFLP’s health organization.” Citing PFLP connections, on June 9, 2015, Israel’s Defense Minister Moshe Ya’alon declared that “the group of people or institutions or association known as the ‘Union of Health Work Committees-Jerusalem [HWC]’…or any other name that this association will be known by, including all of its factions and any branch, center, committee or group of this association is an unauthorized association, as defined by the Defense Regulations” (p.6489). UHWC’s “sister organization” (as referred to by Viva Salud, one of its Belgian partners) in the West Bank and Jerusalem is Health Work Committees (HWC). (For more information on these NGOs’ PFLP ties, read NGO Monitor’s reports “Health Work Committees’ Ties to the PFLP Terror Group” and “Union of Health Work Committees’ Ties to the PFLP Terror Group.”)

Union of Agricultural Works Committees (UAWC)

- Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC) distributed “400 hygiene kits for HHs in vulnerable communities in Area C,” as well as disinfection materials and COVID-19 awareness brochures. UAWC is identified by Fatah as an official “affiliate” and by USAID-engaged audit as the “agricultural arm” of the PFLP terror group. Several UAWC staff members, founders, board members, and general assembly members are tied to the PFLP. This includes Samer Arbid, UAWC’s financial director, indicted and currently standing trial for leading a PFLP terror cell that murdered a 17-year-old Israeli girl in August 2019. (For more information on UAWC’s PFLP ties, read NGO Monitor’s report “Union of Agricultural Work Committees Ties to the PFLP Terror Group.”)

Union of Palestinian Women’s Committees (UPWC)

- According to OCHA, Union of Palestinian Women’s Committees (UPWC) “issued a statement calling on participation of women in emergency committees formed to tackle C19 and to recognize the important role of women in the responses.” UPWC is identified by Fatah as an official PFLP “affiliate” and by a USAID-engaged audit as the “PFLP’s women’s organization.” (See NGO Monitor’s report “Union of Palestinian Women’s Committees Ties to the PFLP Terror Group.”)

Palestinian Center for Human Rights (PCHR)

- Palestinian Center for Human Rights (PCHR), along with Al Mezan, is listed by OCHA as publishing “a position paper on quarantine in Gaza; submitted letters on prisoners’ health and access of families.” PCHR has ties to the PFLP terror group (see NGO Monitor’s report “Palestinian Centre for Human Rights’ Ties to the PFLP Terror Group”).

Palestinian NGO Network (PNGO)

- PNGO’s “health sector” is included in the OCHA appeal on number of projects, including supporting a “24/7 hotline of the MoH in Ramallah and Gaza for COVID-19.” PNGO is Palestinian NGO umbrella organization comprising 135 Palestinian NGO member organizations. The group has, on multiple occasions, expressed its opposition to anti-terror clauses in government grants and in 2017, condemned Norway for pulling funding from a youth center named after Dalal Mughrabi, a terrorist who in 1978 murdered 37 civilians, including 12 children. HWC’s Waleed Hanatsheh (see above) served as a member of PNGO’s board of directors.

Islamic Relief Worldwide (IRW)

- Islamic Relief Worldwide (IRW) delivered “hygiene kits and cleaning tools for persons in quarantine centers: 200 for female (11 items) + 200 for male (12 items)” and provided “daily hot meals to the quarantined persons in Gaza.” On June 19, 2014, Israel’s Defense Minister declared IRW to be illegal, based on its alleged role in funneling money to Hamas, and banned it from operating in Israel and the West Bank. According to news reports, the decision was made after “the Israel Security Agency (Shin Bet), the coordinator for government activities in the territories, and legal authorities provided incriminating information against IRW.” In January 2016, a UK-based bank, HSBC, announced that it was ending all links to IRW, “amid concerns that cash for aid could end up with terrorist groups abroad.”

Funding to NGOs that Promote Violence, Anti-Normalization, and/or Hatred

Burj al Laqlaq

- Burj al Laqlaq is listed as working with “Medecins du Monde France (MDM-F), SAWA, Palestinian Counselling Center (PCC), Madaa, MDMSwiss, and Spafford Centre” on a number of projects, including a “Hotline providing MHPSS services to people under lockdown and victims of domestic violence and abuse,” “Remote sport activities through recorded/live videos in E Jerusalem. Including for 20 children with special needs,” and the dissemination of materials. According to Palestinian Media Watch (PMW), an NGO that reports on incitement, Burj al Laqlaq has a long history of promoting violent messages. For instance, “[in 2012] the Burj Luq-Luq Social Center Society organization performed a puppet show for children in East Jerusalem to promote non-smoking. The educational message delivered by the puppets instructed children to replace cigarettes with machine guns.” According to PMW, Burj Luq-Luq hosted a 2014 soccer tournament named for PLO terrorist Abu Jihad and organized a tournament named for Ibrahim Al-Akari, who murdered two Israeli civilians in a November 2014 attack in Jerusalem.

Ma’an Development Center

- Ma’an Development Center is included in the OCHA funding appeal as a group set to work on projects in the shelter; protection; water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH); and education clusters, and according to Situation Report No. 3, provided “400 gender-sensitive dignity kits.” Ma’an’s “teams are delivering explosive remnants of war risk Education (ERW RE) messages along with Covid19 messages to community residents via street quick sessions.” It is unclear how the two activities, one non-COVID related, relate to one another. Ma’an is active in delegitimization campaigns and is against any “normalization” with Israel. In May 2018, Ma’an Development Center employee Ahmad Abdallah Aladini was killed in the violence on the Gaza border. Aladini was a “comrade” of the PFLP.

Palestinian Medical Relief Society (PMRS)

- Palestinian Medical Relief Society (PMRS) “Distributed health awareness information…350,000 brochures and posters with local partners and authorities. Launched an interactive social media tool run by doctors to answer people’s questions about COVID-19.” In January 2019, Mustafa Barghouti, president of PMRS, participated in a conference organized by the PFLP terror group titled “The crime of normalization and ways of confrontation,” which was held “in honor of the 11th anniversary of the departure of its founder, Dr. George Habash.” During the conference, Barghouti presented a paper on “The role of parties and factions in promoting the boycott concept.” In April 2020, Barghouti condemned American organizations for offering aid that included anti-terror clauses, and called on Palestinian organizations to reject this aid.

Palestinian Center for Democracy and Conflict Resolution (PCDCR)

- The Palestinian Center for Democracy and Conflict Resolution (PCDCR) “Distributed 1,500 awareness posters on the pandemic from UNICEF to partner organizations.” PCDCR refers to Palestinian “victims of Gaza holocaust” and accuses Israel of “state terrorism.”

Funding for Advocacy Activities

As is often the case with OCHA funding requests, counter-productive political projects are part of the “Protection Cluster” component of the appeal. OCHA explains that, in the context of combatting COVID-19, protection is supposed to be primarily focused on training to ensure accurate detection and referral of patients who suffer from Gender Based Violence (GBV) and psychosocial assistance due to GBV. However, the projects being implemented depart from this mandate, with many involving anti-Israel advocacy.

Within the Health Cluster, a number of the projects are being implemented with highly inappropriate NGO partners, and many of the projects themselves are mundane and unrelated to vital aid.

- Under “Ensure right to health is available to all without discrimination,” OCHA lists a “Joint Statement on Israel’s Obligation vis-a-vis West Bank and Gaza in Face of Coronavirus Pandemic” by 18 NGOs– including HRW, PHR-I, B’Tselem, Gisha, and others involved in delegitimization campaigns against Israel. It is difficult to identify how this advocacy statement contributes to ensuring the right to health, particularly one that misstates Israel’s legal obligations and removes any mention of Hamas (or the Palestinian Authority). The NGOs demand “Israel to lift the 13-year closure on Gaza so that inter alia Gaza can equip itself with the necessary medical supplies,” even though, as noted by OCHA in the very same Situation Report, medical supplies are allowed into Gaza. Moreover, at a time when the entire world is implementing closure measures, these NGOs do not explain how lifting such measures on Gaza is good policy during the pandemic.

- As part of “Scale up efforts to mitigate human right violations,” Al Mezan and PCHR published a position paper on “quarantine in Gaza” and “submitted letters on prisoners’ health and access of families.” OCHA links to a very short “news brief” titled “Al Mezan raises key remarks on quarantine measures to the Ministry of Health in Gaza” that praises Hamas efforts to combat COVID-19 as “remarkable.” Al Mezan also “released statement (sic) calling on DFA [De Facto Authorities] to ensure detention under C19 is legally carried out.”

- HaMoked is receiving funding for an “urgent letter demanding Sheikh Sa’ed checkpoint is reopened”; “two urgent letters on impacts of closure on Al Jib checkpoint” and for a “request to High Court for urgent hearing on allowing adult prisoners regular phone contact with families, particularly those in isolation.” HaMoked also “Wrote to the Israel Police about access denial incident” and “Ensured automatic extensions by the Israeli authorities of stay permits.” These short and similar letters, written by a HaMoked attorney and sent to Israel officials, are standard tasks undertaken by the NGO on a regular basis. Additionally, HaMoked “sent an urgent letter to the military demanding that it overturn its arbitrary new policy of barring Palestinian farmers aged 50 or over from entering the seam zone to cultivate their lands.” Given that COVID-19 presents itself more severely in older patients, this policy does not appear “arbitrary.”

- As part of “Scale up efforts to mitigate human rights violations related to COVID-19,” Yesh Din “wrote to the Israeli authorities demanding immediate and increased protection from settler violence.” This type of advocacy is part of the Yesh Din’s regular activities.

- Adalah received funding for an “urgent hearing to the Israeli High Court of Justice against Israeli MoH demanding COVID-19 testing for 150,000 Palestinians living in Kfar Aqab and Shuafat refugee camp.” Adalah also received funding for a number of letters to various Israeli government ministries. Such petitions before the Israeli courts and letters are standard activities for Adalah.

- B’Tselem received funding for a “press release analysing settler violence spike exploiting COVID-19.” Such press releases are standard activities for B’Tselem.

- Situation Report No. 3 (1-6 April) explains that “partners working on prisoners’ issues” “filed a petition demanding the release of Palestinian prisoners at risk in Israeli prisons”; that “Six Israeli and Palestinian human rights organizations” “issued a joint statement expressing concern for the health and life of prisoners in Israel”; and that “Legal aid partners” filed “a petition to the Israeli High Court of Justice” so “Palestinian minors in detention [could make] pre-approved firstdegree relative phone calls, once a fortnight for ten minutes.” Reflecting a lack of transparency, NGO partners are not named.6 More generally, prisoners is a common theme in standard anti-Israel advocacy efforts of Palestinian NGOs, which claim that all Palestinian prisoners, including violent terrorists, are “political prisoners.” This lack of transparency is especially concerning given that a number of NGOs involved in these campaigns have ties to the PFLP terror group.

- The Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI) submitted at least 35 appeals and petitions to different Israeli government ministries, including the Postal Bank and Ministry of Defense. These included ACRI “joining” a letter “with other human rights organizations to Benny Gantz and the Blue and White Party demanding that they fulfil their promise to rpotect (sic) democratic instuttions (sic) and upohold (sic) the rule of law.” These types of petitions are part of the NGO’s standard advocacy and many have nothing to do with humanitarian responses to COVID-19.

Non-Emergency Measures Receiving Scarce Resources

Some of the OCHA funding is for mundane activities, such as printing materials and sending messages. In principle, these activities are not inherently objectionable and may make a contribution on some level to outbreak prevention.

However, the involvement of international humanitarian NGOs in such efforts raises a number of questions: Why, if there is an acute medical crisis, are international groups with real expertise relegated to negligible tasks? If there are scarce resources requiring the raising of emergency funds, why are these activities even included? Why are massive, wealthy NGOs apparently receiving funds for them? And how are international groups necessary in this context, when there are local authorities and a plethora of local NGOs?

These activities suggest that, for OCHA, it is more important to maintain the relevance of NGOs and keep them in business than to use available resources efficiently.

- UHWC published “Facebook posts on UHWC Facebook account.”

- Médecins du Monde-France and War Child Holland are receiving funds for the “Dissemination of ERW and C19 messaging to herder and Bedouin communities at UXO risk, using Whatsapp and leaflets.” It is unclear what costs are associated with sending Whatsapp messages.

- World Vision provided PPE materials as well as “Provided promotional material about COVID-19: 50,000 brochures, 50,000 fliers, 5,000 posters, and 150 roll ups” and posted and shared “COVID-19 related messages through social media.”

- Médecins du Monde disseminated “awareness messages through network of 5 CBOs, 8 emergency committees and 5 social media platforms following the RCCE taskforce weekly messages” and was involved in “MHPSS including individual counselling, and awareness raising.”

- UAWC distributed “270,000 seedlings for approximately 2,500 household gardens in more than 74 communities, providing vegetable seedlings as well as, training families on how to grow these seedlings and also how to protect themselves against CoronaVirus in the garden and the house.”

Recommendations

To OCHA and WHO:

- Cease all cooperation with NGOs with personnel who have ties to terrorist organizations (as defined by donor states), including those with links to the PFLP.

- Ensure partners selected for implementing emergency response plans adhere to codes of conduct for humanitarian organizations – including “do no harm.”

- Provide greater transparency as to how funds are allocated.

- End funding to advocacy projects, particularly during emergencies, in order to prioritize vital life-saving measures.

- Reallocate all funding used for political advocacy to building essential humanitarian infrastructure.

To Donor Governments:

- Develop and implement robust funding guidelines for all government spending to ensure that funds are not provided to groups with ties to terrorism or that promote violent rhetoric or antisemitism.

- Review all funding to OCHA and WHO projects to guarantee that funds are not being distributed to NGOs with ties to terrorist organizations.

- Ensure that UN bodies respect and adhere to domestic terrorism legislation and terror entity lists.

- Ensure that funding is used solely for humanitarian purposes.

- Institute continuous monitoring mechanisms to ensure ongoing compliance with these best practices.

Footnotes

- Independent of OCHA’s Response Plan, UNRWA (UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) is seeking $93 million for its March – July 2020 “flash appeal for the covid-19 response.” It is unclear whether there is overlap between these two funding appeals, especially considering that UNRWA is an OCHA implementing partner on a number of projects and is included as being part of the “joint strategy” for the Response Plan.

- According to OCHA, “a revised version of the COVID-19 Inter-Agency Response Plan for the oPt, originally launched on March 26, was release on April 25… the updated requirement is $42.4 million, up from $34 million in the original version.” OCHA explains that “The additional $7 million is to provide support to quarantine centers in Gaza and the West Bank; multi-sectoral efforts in East Jerusalem; and safety net support for most vulnerable communities.”

- The PFLP is a designated terrorist organization in the US, EU, Canada, and Israel. The PFLP is involved in suicide bombings, shootings, and assassinations, among other terrorist activities targeting civilians, and was the first Palestinian organization to hijack airplanes in the 1960s and 1970s.

- In Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza, UNICEF partners with a number of terror-tied NGOs and organizations that promote delegitimization campaigns against Israel. See NGO Monitor’s report, “UNICEF and its NGO Working Group,” for details.

- For example, Kuwait was originally listed as providing $9 million in “new” funding and is now providing just $747,500 “through the response plan” with balance for “outside the response plan.” Likewise, OCHA originally claimed the EU had “reprogrammed” $7.8 million for the Response Plan; later, OCHA indicated that this allocation may not reflect donor wishes, as “attribution to the Inter-Agency COVID-19 Response Plan (sic) under verification.” Canada originally was giving $2.8 million to the Response Plan, was later listed as providing $1.8 million “Outside the Response Plan,” and is now listed as providing $1.9 million “Through the Response Plan.”

- NGO Monitor research shows that the “Six Israeli and Palestinian human rights organizations” are likely Physicians for Human Rights Israel, Association for Civil Rights in Israel, Al Mezan, Hotline for Refugees and Migrants, HaMoked, and Public Committee against Torture in Israel.